Quick start

Installation

See the Installation section.

Create a project

Create a new project with this command:

cargo creusot new project-name

Note

If you are using the development version of Creusot (

masterbranch), you should also point your project to your local copy ofcreusot-std, using the--creusot-stdoption (otherwise the default is to use the released version on crates.io). To avoid hard-coding local paths in your configuration, one approach is to set--creusot-std creusot-std, and make a symbolic linkcreusot-stdpointing to your localcreusot-std.

That command creates a directory package-name containing the basic elements of a Rust project verified with Creusot. The file src/lib.rs is initialized with an example function annotated with a contract:

// src/lib.rs

use creusot_std::prelude::*;

#[requires(x@ < i64::MAX@)]

#[ensures(result@ == x@ + 1)]

pub fn add_one(x: i64) -> i64 {

x + 1

}Compile and prove

To verify this project, run this command:

cargo creusot prove

A successful run gives us the certainty that functions defined in this package satisfy their contracts:

for all arguments satisfying the preconditions (requires clauses), the result of the function will

satisfy the postconditions (ensures clauses).

The command cargo creusot prove does two things: compile your Rust crate to Coma, then search for

proofs of verification conditions generated from the Coma code using Why3find. These steps can be performed separately.

-

Run only the compiler and obtain Coma code:

cargo creusot -

Run Why3find’s proof search only on a specific Coma file (by default, Why3find is run on all Coma files under the

verif):cargo creusot prove verif/[COMA_FILE]Multiple files can also be specified in a single command.

When the proof fails, you can add the -i option to open the Coma file in Why3 IDE.

cargo creusot prove verif/[COMA_FILE] -i

The -i option only launches the Why3 IDE if the proof fails.

You can also use --ide-always

cargo creusot prove verif/[COMA_FILE] --ide-always

When you know that the proof is going to fail, it can be slow to update every time you modify your code.

To skip proof search and just reuse the existing proof.json as is, add the option --replay.

cargo creusot prove verif/[COMA_FILE] --ide-always --replay

The documentation for the Why3 IDE can be found here.

We also recommend section 2.3 of this thesis for a brief overview of Why3 and Creusot proofs.

Troubleshooting

If you get an error like this

error: The `creusot_std` crate is loaded, but the following items are missing: <a list of identifiers> Maybe your version of `creusot-std` is wrong?

Add the following to your Cargo.toml file:

[patch.crates-io]

creusot-std = { path = "/relative/or/absolute/path/to/creusot-std/in/creusot/directory" }

And please notify the Creusot developers that the version of Creusot should be bumped to NEXT_VERSION-dev to prevent this error.

Legacy workflow with Why3 IDE

This workflow is intended to help projects using old versions of Creusot that still use why3session.xml.

Run the Creusot compiler:

cargo creusot

Launch the Why3 IDE:

cargo creusot why3 ide [FILE]

You must specify a file why3session.xml or a Coma file.

Difference with cargo creusot prove:

cargo creusot prove(with-ior--ide-always) runs the Creusot compiler and the Why3find proof search beforehand, ensuring that you’re always working on the latest version of your code.cargo creusot why3 ideonly runswhy3 idewith the necessary options to load Coma files produced by Creusot. It’s up to you to make sure that the Coma files are up-to-date.

Editor configuration

From the root of your project, write the following in the .vscode/settings.json file:

{

"rust-analyzer.check.overrideCommand": [

"cargo",

"creusot",

"--",

"--message-format=json"

]

}

For other editors, see https://rust-analyzer.github.io/book/other_editors.html to add the above option to your configuration.

Note that you will probably want to enable this option only in projects that use creusot.

Installation

This section explains how to install Creusot, what goes into the installation, and some configuration options.

Quick installation (using custom script)

The INSTALL script installs Creusot and its accompanying tools.

Requirements to run the INSTALL script:

cargoopamto installwhy3andwhy3find.curlto download provers:alt-ergo,z3,cvc4,cvc5.

./INSTALL

See ./INSTALL --help for options.

Note that the INSTALL script will take a couple minutes to create

a local Opam switch and then to install the many dependencies of why3.

The local switch will be located in $XDG_DATA_HOME/creusot/_opam

(default on Linux: ~/.local/share/creusot/_opam). We recommend having this local

switch to prevent accidentally breaking your Creusot setup while working

on other OCaml projects.

Quick installation (using nix)

If you are using nix, you do not need to have a copy of this repository.

We assume that you have nix installed on your system. Setup instructions can be found here: https://nixos.org/download

You can use nix shell to enter an interactive subshell containing the project:

nix shell "github:creusot-rs/creusot"

The project lives in this subshell and will disappear as soon as you leave the subshell.

If you do not have flakes enabled, you may get this error:

error: experimental Nix feature 'nix-command' is disabled; use ''--extra-experimental-features nix-command' to override

All you have to do is activate flakes temporarily by using --extra-experimental-features 'nix-command flakes':

nix --extra-experimental-features 'nix-command flakes' shell "github:creusot-rs/creusot"

Manual installation

-

You can install the core files from the Creusot repository with Cargo alone:

# Install cargo-creusot cargo install --path cargo-creusot # Install creusot-rustc TOOLCHAIN=$(grep "nightly-[0-9-]*" --only-matching rust-toolchain) cargo install --path cargo-creusot --root $XDG_DATA_HOME/creusot/toolchain/$TOOLCHAIN/bin # Install the Creusot prelude cargo run --bin prelude-generator mkdir -p $XDG_DATA_HOME/share/why3find cp -rT target/creusot/packages $XDG_DATA_HOME/share/why3find/packages # Copy why3find.json in the installation directory cp cargo-install/why3find.json $XDG_DATA_HOME/creusot/why3find.json -

The following binaries must then be put in

$XDG_DATA_HOME/creusot/bin, refer to their respective project pages for how to get them:

Installed files

Everything Creusot needs to run.

-

cargo-creusotinPATH. This is the entry point of Creusot. -

$XDG_DATA_HOME/creusot/(default on Linux:~/.local/share/creusot), a directory containing:-

toolchain/$TOOLCHAIN/bin/creusot-rustc, the Creusot compiler, where$TOOLCHAINis the toolchain used to build Creusot (set by the filerust-toolchainin the Creusot repository). -

bin/containing binaries.why3andwhy3find- Provers:

alt-ergo,z3,cvc5,cvc4

-

why3find.json, which is used to create new Creusot projects withcargo creusot neworcargo creusot init. -

share/why3find/packages/creusot/creusot/: the Creusot prelude (a Coma library).

-

Why3

The Why3 configuration is located at $XDG_CONFIG_HOME/creusot/why3.conf

(default on Linux: ~/.config/creusot). This file is generated by cargo creusot prove

if it does not already exist, and by cargo creusot why3-conf. Notable options in this file:

- the location and version of provers (

[partial_prover]) (for the Nix installation, this is not known during the installation of Creusot, that’s why this file is generated later). - The maximum number of parallel prover jobs (

running_provers_max = ...). [strategy]for solving goals in Why3 IDE.[ide]options for Why3 IDE (can be modified in the menuFile > Preferences).

Why3find

cargo creusot prove invokes why3find, which looks for the file why3find.json in the current working directory or one of its parents.

At the moment we recommend not modifying why3find.json. Instead, you should rely on adapting your Rust code to make proofs more robust, for example by adding more assertions.

Please open an issue if this configuration does not work for you.

Nevertheless, you may like to experiment with some of these options:

"fast"and"time": timeout durations in seconds for provers."depth": proof search is pruned after this number of levels."tactics": list of tactics to apply during proof search. “Tactics” are Why3 transformations that take no arguments. For example:compute_in_goalandinline_goalare tactics;apply H,exists Xare not tactics.

See the Why3find README for more information.

Tutorial

This tutorial is an introduction to deductive verification with Creusot. After introducing basic concepts, we will walk through the steps to verify a function with Creusot.

No prior knowledge about formal methods is required to follow this tutorial. Basic familiarity with Rust should be enough to get started with Creusot.

Creusot

Follow the README to install Why3 and Creusot.

Setup

Create a new project with this command:

cargo creusot new creusot-tutorial

This generates a directory creusot-tutorial containing the following files:

Cargo.toml

why3find.json

src/lib.rs

The first two files contain package-level configuration settings. You’re most likely already familiar with

Cargo.toml. why3find.json is

used by a verification tool invoked by Creusot. We will leave these files alone for this tutorial.

The last file, src/lib.rs, is what we will be editing in this tutorial.

My first contract

Open src/lib.rs. It contains an example function with a contract:

use creusot_std::prelude::*;

#[requires(x@ < i64::MAX@)]

#[ensures(result@ == x@ + 1)]

pub fn add_one(x: i64) -> i64 {

x + 1

}In Creusot, contracts are how we specify the expected behavior of functions. A contract contains two kinds of assertions: preconditions, or “required clauses”, describe the values of arguments that the function accepts; postconditions, or “ensured clauses”, describe the result value that the function returns.

In this first example, there is one precondition (requires) and one postcondition (ensures).

This contract can be read as follows: if the argument x is smaller than i64::MAX,

then the value of add_one(x) will be equal to x@ + 1.

More generally, a function satisfies its contract when, for any input arguments that satisfy

the preconditions (requires), the result of the function satisfies the postcondition (ensures).

It is not a very exciting contract, since it just replicates the body of the function x + 1.

But note that x@ + 1 is not exactly the same expression. The @ suffix is Creusot’s view operator,

which maps a Rust value to a mathematical value. If x has type i64, then x@ has type Int,

as the type of mathematical integers (…, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, …).

The key difference is that mathematical integers are unbounded: their arithmetic operations do not overflow.

They are more intuitive and better behaved than operations on machine integer.

For example, all x: Int satisfy x < x + 1 whereas this cannot be true for Rust’s machine integers because they are finite.

The type Int is one of several built-in types of common mathematical objects defined by Creusot;

others include sequences and mappings (mathematical functions).

On the one hand, mathematical objects like Int cannot be manipulated by Rust programs, they can only be used in contracts.

On the other hand, values that exist in Rust programs such as machine integers (i64, etc.) are not as easy to manipulate

in the logical world of contracts, so we use the view operator @ to transform them into something more intuitive.

The contract of add_one specifies the result slightly indirectly: its view as an unbounded integer, denoted by result@,

must be equal to x@ + 1. Note that arithmetic operations are only defined on Int in the logical world of contracts.

Verifying the contract

cargo creusot prove

First, the Rust code is compiled to Coma, an intermediate verification language in the Why3 platform. Second, Why3 verifies the compiled program by generating verification conditions and sending them as queries to SMT solvers. When all verification conditions have been proved, that amounts to proving that functions defined in our crate satisfy their contracts.

My second contract

Here is a more involved example: given a non-negative integer n, compute the sum of all integers between 0 and n included.

We can do this simply by iterating through each integer up to n. This is the function to verify.

pub fn sum_up_to(n: u64) -> u64 {

let mut sum = 0;

let mut i = 0;

while i < n {

i += 1;

sum += i;

}

sum

}Although a for loop would be idiomatic, that also adds some complications to the verification process.

For the sake of simplicity, we start with a while loop, and switch to a for loop at the end.

As a sanity check, we can write unit tests:

#[test]

pub fn test_sum_up_to() {

// 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 = 10

assert_eq!(sum_up_to(4), 10);

}Run with

cargo test

Whereas unit tests let us check the output associated with specific inputs of a function, contracts let us specify the output for all possible inputs. Naturally, we can’t exhaustively list input-output pairs. Instead, we describe the relation between inputs and outputs as properties, logical formulas that are true about the inputs and outputs of a function.

Contract

The result of this sum is also known as the triangular numbers,

with a well-known formula: n * (n + 1) / 2. This provides a nice and concise specification for sum_up_to.

Write an #[ensures(...)] clause to give a postcondition to sum_up_to using the formula for triangular numbers.

Added postcondition

#[ensures(result@ == n@ * (n@ + 1) / 2)]

pub fn sum_up_to(n: u64) -> u64 {

// ...

}Run cargo creusot to make sure that the postcondition is well-formed.

Of course, cargo creusot prove will fail. The contract is still too naive at this point.

What if the sum overflows? Feel free to try different approaches to handle this problem. Here is a non-exhaustive list of possibilities.

Add a simple bound on the input as a precondition

#[requires(n@ < 1000)]

#[ensures(result@ == n@ * (n@ + 1) / 2)]

pub fn sum_up_to(n: u64) -> u64 {

// ...

}Add a more precise upper bound as a precondition

#[requires(n@ * (n@ + 1) / 2 <= u64::MAX@)]

#[ensures(result@ == n@ * (n@ + 1) / 2)]

pub fn sum_up_to(n: u64) -> u64 {

// ...

}Allow overflows and adjust the postcondition accordingly

#[ensures(result@ == (n@ * (n@ + 1) / 2) % (u64::MAX + 1))]

pub fn sum_up_to(n: u64) -> u64 {

// ...

}Change the result type to be big enough

#[ensures(result@ == n@ * (n@ + 1) / 2)]

pub fn sum_up_to(n: u64) -> u128 {

// ...

}At this point, you may have a contract that is satisfied by the function,

but cargo creusot prove still can’t verify it. This function contains a loop,

and loops must be annotated with loop invariants: assertions which must be true

at every iteration of the loop.

Loop invariants

A loop invariant looks like this:

#[invariant(i@ <= n@)]

while i < n {

i += 1;

sum += i;

}At every step, i is less than or equal to n. In particular, it is true when we enter the loop (when i = 0),

inside the loop body it must have been that i < n, which gives us i+1 <= n, with i+1 as the next value of i,

and when we exit, the loop condition i < n is false, which combined with the invariant i@ <= n@ tells us that i = n

when the function returns. We could have written this invariant as i <= n, without the @.

Inspecting proofs with Why3 IDE

The invariant is still incomplete.

To investigate what’s missing, we can inspect proofs in progress with Why3 IDE.

The command cargo creusot prove with the -i option launches Why3 IDE, showing

the proof state for an as yet unverified function.

cargo creusot prove -i

If there are many functions to verify, we can pick a specific one on the command line

by naming the Coma file it was compiled to. Coma files are generated in the verif/ directory,

and their path consists of the crate name (creusot_tutorial_rlib for the library creusot-tutorial)

followed by the fully qualified function name (creusot_tutorial::sum_up_to becomes creusot_tutorial/sum_up_to.coma).

cargo creusot prove -i verif/creusot_tutorial_rlib/creusot_tutorial/sum_up_to.coma

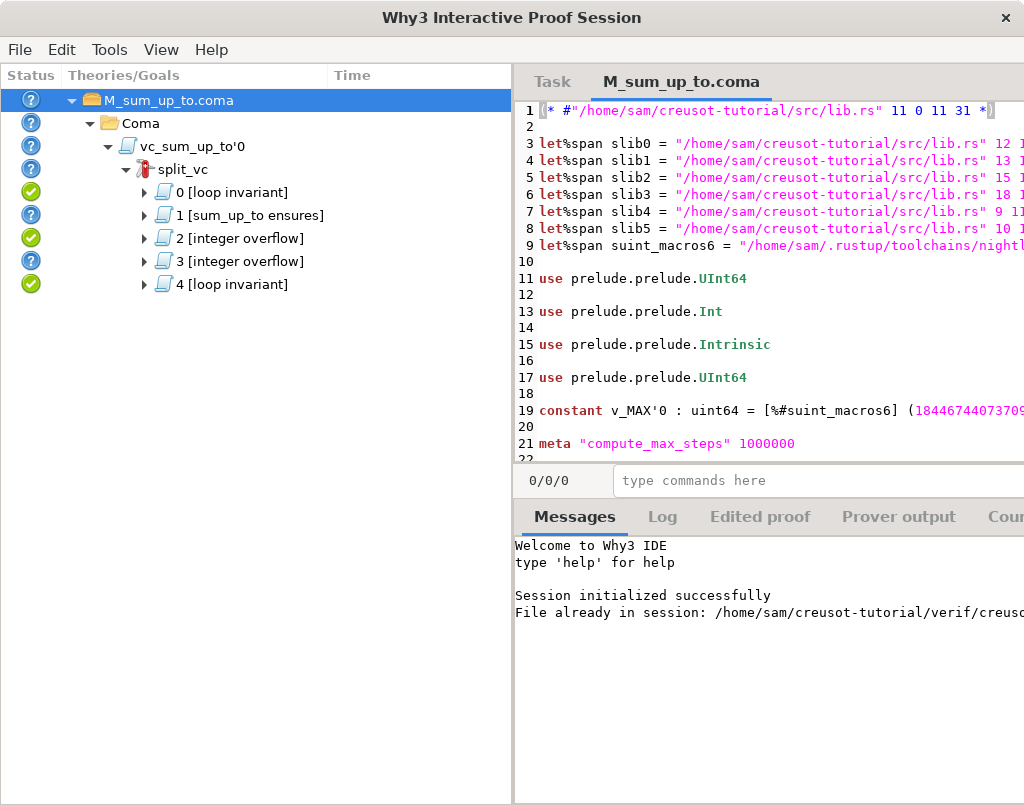

Why3 IDE is a GUI that looks like this:

It’s a three-pane window. The left panel displays the tree of goals to prove. The top right panel displays the proof context, which consists of relevant source files and a special Task tab listing available hypotheses and the goal formula. The bottom right panel contains error messages and other logs.

In the left panel, the status of every tree node is shown as an icon in the leftmost column.

Goals with complete proofs have green checkmarks, unproved goals have blue question marks.

Currently, the bottom of the tree consists of five subgoals labeled [loop invariant],

[sum_up_to ensures], [integer overflow] twice, and [loop invariant] again.

To verify that a function satisfies its contract, Why3 generates verification conditions which represent properties that must hold at certain points in the program:

-

Starting from the top of the function

sum_up_to, we must check that the loop invariant holds when we enter the loop, that corresponds to the first[loop invariant]goal. -

Inside the loop, we show that any iteration of the loop body preserves the loop invariant: we start with arbitrary values of

iandsumassuming that the loop invariant holds and that the conditioni < nis true. Checking thati += 1does not overflow corresponds to the first[integer overflow]goal. Checking thatsum += idoes not overflow corresponds to the second[integer overflow]goal. -

At the end of the loop body the invariant must hold again, corresponding to the last

[loop invariant]goal.

Finally, at the loop exit, we assume that the loop invariant holds and that the condition i < n is false,

and prove that the returned value satisfies the postcondition (ensures clause), which corresponds to the

[sum_up_to ensures] goal. It may seem surprising that the goal [sum_up_to ensures] appears first even though

it corresponds to the end of the function;

this is due to internal details of compiling the program to a control-flow graph and generating verification

conditions by traversing the control-flow graph in a somewhat arbitrary order.

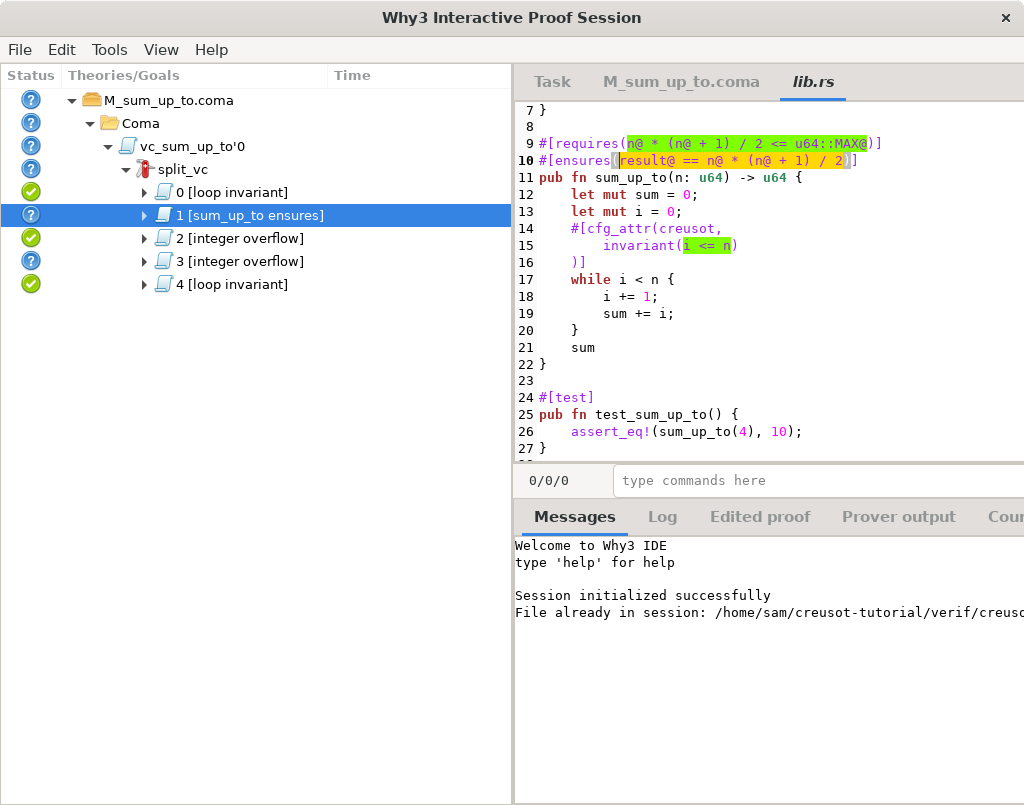

One way to make sense of the goals is to look at the source spans they contain.

In the left panel, click on the goal labeled [sum_up_to ensures].

That opens a tab lib.rs on the top right panel; click on it.

We see a view of the Rust code we are trying to verify,

with highlighted spans relevant to the goal we selected.

What we are trying to prove is highlighted in yellow:

the goal [sum_up_to ensures], as its name indicates, is trying to prove that the

ensures clause holds when the function returns.

Hypotheses and various bits of code that the goal depends on are highlighted in green:

the requires clause and the loop invariant are hypotheses.

Similarly, you can inspect the two [loop invariant] goals. Both will highlight

the invariant i <= n in yellow, but there will be a difference in the surrounding spans:

one goal will highlight the 0 from the initialization of i, indicating that the goal

comes from entering the loop, whereas the other goal will highlight the 1 in the

increment i += 1, indicating that the goal comes from checking that the loop body maintains the

loop invariant.

It is easy to prove that the addition in i += 1 will not overflow, because the loop condition i < n

is true. However we cannot deduce that the addition in sum += i will not overflow yet, because

we know nothing about sum in the loop invariant.

For that same reason, there is also no way to prove the postcondition ([sum_up_to ensures]).

Complete the loop invariant

Complete the invariant. Below we extended the invariant with a placeholder for your solution.

Intuitively, the invariant should reflect the idea that at every step, sum is the sum of numbers from 0 to i included.

#[invariant(i@ <= n@)]

#[invariant(true /* YOUR INVARIANT HERE */)]

while i < n {

i += 1;

sum += i;

}Completed invariant

#[invariant(i@ <= n@)]

#[invariant(sum@ == i@ * (i@ + 1) / 2)]

while i < n {

i += 1;

sum += i;

}With that, cargo creusot prove succeeds. We have proved that the function sum_up_to satisfies its contract.

Complete sum_up_to function with all annotations

#[requires(n@ * (n@ + 1) / 2 <= u64::MAX@)]

#[ensures(result@ == n@ * (n@ + 1) / 2)]

pub fn sum_up_to(n: u64) -> u64 {

let mut sum = 0;

let mut i = 0;

#[invariant(i@ <= n@)]

#[invariant(sum@ == i@ * (i@ + 1) / 2)]

while i < n {

i += 1;

sum += i;

}

sum

}Use a for loop

The while loop above can be replaced with a more idiomatic for loop.

for i in 1..=n {

sum += i;

}Verifying a for loop is more complicated because we must reason about iterators.

Another challenge is that the invariant cannot talk about the next value (i):

there might not be a next value.

Creusot defines a special variable, produced, which contains the sequence of elements

previously produced by the iterator of a for loop.

Using that variable, we can restate the invariant about sum:

#[invariant(sum@ == produced.len() * (produced.len() + 1) / 2)]

for i in 1..=n {

sum += i;

}Indeed, produced.len() is exactly the number of past iterations.

We no longer need the other clause of the invariant, i <= n,

first because i isn’t even in scope in the invariant,

and also because that fact will be deduced automatically from the

postcondition of next for the iterator 1..=n, which is where i comes from.

We are almost done. In principle, that invariant should be all we need to complete the proof. But the solvers can’t figure it out for some reason. It may be that solvers have trouble with division. We can tweak the invariant to avoid relying on division, and the proof goes through.

#[invariant(sum@ * 2 == produced.len() * (produced.len() + 1))]

for i in 1..=n {

sum += i;

}This kind of wrinkle is par for the course in SMT-based tools such as Creusot.

Complete sum_up_to function with all annotations (for loop version)

#[requires(n@ * (n@ + 1) / 2 <= u64::MAX@)]

#[ensures(result@ == n@ * (n@ + 1) / 2)]

pub fn sum_up_to(n: u64) -> u64 {

let mut sum = 0;

#[invariant(sum@ * 2 == produced.len() * (produced.len() + 1))]

for i in 1..=n {

sum += i;

}

sum

}Conclusion

In this tutorial, we’ve got a glimpse of the workflow of verifying a Rust program in Creusot.

We have only scratched the surface. Creusot offers many more features for verifying Rust code at large. You can read about them in the rest of this user guide.

Gnome sort

Important

Get the starting code for this tutorial in the creusot-rs/tutorial repository.

Open the file

src/ex1_gnome_sort.rs.

Gnome sort is a sorting algorithm with the simplicity of a single while loop.

pub fn gnome_sort(v: &mut [usize])

{

let mut n = 0;

while n < v.len() {

if n == 0 || v[n - 1] <= v[n] {

n += 1;

} else {

v.swap(n - 1, n);

n -= 1;

}

}

}Starting from index n = 0, we increment n as long as

we encounter successive elements in increasing order.

When we find an element v[n] out of order (v[n] < v[n-1]),

we insert it into the preceding sorted prefix by repeated swaps of adjacent elements.

Step 1: Specification

Write the contract of gnome_sort, using the #[ensures] attribute.

There are two postconditions to formalize:

- The final slice

^vcontains elements in increasing order. - The final slice

^vcontains the same elements as the initial slicev.

After having written your specification, you should be able to compile the project (with the command cargo creusot). But of course the proof attempt will fail (with the command cargo creusot prove).

Tip

- Universal quantification is written as

forall<i>(or with a type annotation,forall<i: Int>). Implication is written as==>.- To access the elements of a slice in logic, use the view operator

@. The termv@denotes the finite sequence of elements contained in the slicev, andv@[i]denotes thei-th element of that sequence.- The second postcondition is just

(^v)@.permutation_of(v@). (Actually spelling this out is rather complicated and besides the point of this tutorial.)

Solution

#[ensures(forall<i,j> 0 <= i && i < j && j < v@.len() ==> (^v)@[i] <= (^v)@[j])]

#[ensures((^v)@.permutation_of(v@))]Step 2: Loop invariant

To help Creusot prove that the contract is valid, we want to write a suitable loop invariant. There will be two clauses to the invariant, mirroring the desired postconditions we just wrote:

- The first

nelements ofvare in increasing order. - The current slice

vcontains the same elements as the old slice (i.e., the initial value of the slice).

To be able to refer to the old slice, take a snapshot of v before entering the loop:

let old_v = snapshot!{ v };A snapshot is a purely logical construct. Its value can only be

accessed in specifications. During execution, a snapshot behaves like

the unit ().

Now, old_v has type Snapshot<&mut [usize]>, so we can refer to the

initial value as **old_v in Pearlite (one * for Snapshot,

and one * for &mut).

Annotate the while loop with its invariant(s), using the #[invariant] attribute.

With this, the command cargo creusot prove should succeed.

You have formally verified the functional correctness of a sorting function.

Solution

#[invariant(forall<i,j> 0 <= i && i < j && j < n@ ==> v@[i] <= v@[j])]

#[invariant(v@.permutation_of((**old_v)@))]Step 3: Polymorphism

The function gnome_sort is currently restricted to elements of type usize.

Let’s generalize gnome_sort to elements of any type that implements the comparison operation (<=).

In other words, we can sort slices of any totally ordered type.

In Rust, totally ordered types implement the Ord trait.

In Creusot, we also require such types T to implement the trait

DeepModel, and for the associated type T::DeepModelTy to

implement OrdLogic, which is the “logical” equivalent of Ord:

OrdLogic defines the meaning of <= in Pearlite.

Although this looks convoluted, this makes it easier to specify and

verify implementations of Ord for complex data structures.

With this generalization, we will also need to modify the #[ensures] and

#[invariant] clauses. Instead of directly comparing elements of the slice

(v@[i] <= v@[j]), we will compare their deep models

(v@[i].deep_model() <= v@[j].deep_model()).

Solution

pub fn gnome_sort<T>(v: &mut [T])

where

T: Ord + DeepModel,

T::DeepModelTy: OrdLogic,

{

/* ... */

}Conclusion

We have proved the functional correctness of Gnome sort. Then we generalized it to sort elements of arbitrary ordered types.

Bonus challenge (non-trivial!): prove the termination of gnome_sort. See the Termination chapter for more information.

Linked list

Important

Get the starting code for this tutorial in the creusot-rs/tutorial repository.

Open the file

src/ex2_linked_list.rs.

This tutorial demonstrates how we can use Creusot to verify

a data structure manipulating raw pointers.

This data structure uses unsafe blocks to dereference raw pointers,

and we can prove that these operations are in fact safe.

A linked list provides an efficient implementation for a queue:

the operations push_back and pop_front can be performed in constant time.

Moreover, the push_front operation is also available in constant time.

To support constant-time push_back and pop_front, we must be able to

access and modify the linked list from both ends. For that reason,

this data structure is inherently challenging to express in safe Rust.

Hence, we implement this linked list using raw pointers.

A linked list is made of multiple links.

Each Link contains a value and a raw pointer to the next Link.

This pointer may be null, which indicates the end of the list.

struct Link<T> {

value: T,

next: *const Link<T>,

}We keep track of a linked list with two pointers: they point to the first

and last links. If we start from the first link and repeatedly follow

next pointers, we will eventually reach the last link, and

its next pointer must be null.

pub struct List<T> {

first: *const Link<T>,

last: *const Link<T>,

}This type implements the following methods:

-

push_back(&mut self, value: T): allocate a newlink: Link<T>, make thenextfield of the currentlastlink point to the newlink, and changelasttolink. -

pop_front(&mut self) -> T: take out thefirstlink, and changefirstto thenextlink. -

push_front(&mut self, value: T).

Step 1: Ghost permissions

To verify pointer operations, Creusot provides the notion of ghost permissions. A permission is a token which keeps track of the data associated with a pointer. This token cannot be duplicated: we leverage Rust’s ownership system to reason about pointer aliasing. Permissions are a ghost resource, which means that they have no run-time impact; their only use is to enable formal verification. Pointer permissions play a similar role to points-to assertions in separation logic.

The first step is to make permissions explicit in the data structure.

Extend the List type with a Ghost field containing the permissions for the pointers contained in the linked list.

Tip

- The type of permissions for pointers

*const TisPerm<*const T>.Permis an unsized type; we can put it in aBoxwhen a sized type is expected.- As a linked list is essentially a sequence of

Link<T>, we can store permissions in a sequence (Seq).- To make it compile, we will also need to update

List::new()to callSeq::new()to conjure an empty ghost sequence.

Solution

pub struct List<T> {

first: *const Link<T>,

last: *const Link<T>,

/// Pointer permissions of all list links

seq: Ghost<Seq<Box<Perm<*const Link<T>>>>>,

}

impl<T> List<T> {

pub fn new() -> List<T> {

// Initialize the `seq` field with an empty `Seq`.

List { first: std::ptr::null(), last: std::ptr::null(), seq: Seq::new() }

}

}Step 2: Type invariant

The permissions in a List<T> should correspond to the pointers that it contains.

Write a type invariant, by implementing the Invariant trait, to encode this well-formedness condition.

It contains one method invariant(self)

which defines the property that all values of that type should satisfy.

Creusot will automatically assume type invariants of function parameters as additional preconditions, and type invariants of results as additional postconditions. For functions that take mutable borrows as arguments, type invariants are assumed for the initial value as preconditions, and asserted as postconditions for the final value.

Tip

- A permission

Perm<*const T>contains two pieces of data: the.ward(), which is the pointer protected by the permission, and the value (.val()) that the pointer points to.self.firstmust point to the first element: it must be thewardof the first element ofself.seq. Similarly,self.lastmust be thewardof the last element ofself.seq.- The links must be chained properly: each link’s

nextpointer must be the ward of the next link inself.seq, except for the last link, whosenextmust be null. (Hint: useis_null_logic.)- Don’t forget the base case!

Solution

impl<T> Invariant for List<T> {

#[logic(inline)]

fn invariant(self) -> bool {

pearlite! {

(*self.seq == Seq::empty() &&

self.first.is_null_logic() &&

self.last.is_null_logic())

||

(self.seq.len() > 0 &&

self.first == *self.seq[0].ward() &&

self.last == *self.seq[self.seq.len() - 1].ward() &&

// the links in `seq` are chained properly

(forall<i> 0 <= i && i < self.seq.len() - 1 ==>

self.seq[i].val().next == *self.seq[i+1].ward()) &&

self.seq[self.seq.len() - 1].val().next.is_null_logic())

}

}

}Step 3: View

To formalize the functional correctness of List methods, it is convenient

to have a functional model for it, also known as a view in Creusot.

Implement the View trait to define a view.

A linked list naturally represents a sequence of elements: we define the view

of linked lists as a mapping from List<T> to sequences Seq<T>.

Thus, a view provides a high-level representation of a data structure,

hiding the details of memory layout.

Tip

- Use the

Seq::mapmethod.- The body of

#[logic]functions should be wrapped in thepearlite!macro.

Solution

impl<T> View for List<T> {

type ViewTy = Seq<T>;

#[logic]

fn view(self) -> Self::ViewTy {

pearlite! {

(*self.seq).map(|ptr_perm: Box<Perm<*const Link<T>>>| ptr_perm.val().value)

}

}

}We are now ready to verify the methods of List.

Step 4: new

Write the contract of new(): the view of the result is the empty sequence Seq::empty().

Solution

#[ensures(result@ == Seq::empty())]Step 5: push_back

Specify push_back

Write the contract of List::push_back.

Tip

Use

Seq::push_back.

Solution

#[ensures((^self)@ == (*self)@.push_back(value))]Verify push_back

We must rewrite the body of the function slightly to make use of the permissions that we’ve made explicit. There are three things to do:

- Replace

Box::into_raw, which casts the newly allocatedBoxinto a pointer, withPerm::from_box, which also returns the associated permission with it. - Replace the raw pointer dereference

*(self.last as *mut Link<T>)withPerm::as_mut, which requires the pointer’s permission. - Push the permission (from

Perm::from_box) intoself.seq. (Hint:Seqimplements thepush_backmethod.)

Tip

For steps 2 and 3, use

ghost!blocks: they enable calling ghost functions (Seq::len_ghost,Seq::get_mut_ghost,Seq::push_back_ghost,Ghost::into_inner) and they are erased at run time.

Solution

pub fn push_back(&mut self, value: T) {

let link = Box::new(Link { value, next: std::ptr::null() });

let (link_ptr, link_own) = Perm::from_box(link); // 1

if self.last.is_null() {

self.first = link_ptr;

self.last = link_ptr;

} else {

let link_last = unsafe {

Perm::as_mut(

self.last as *mut Link<T>,

ghost! { // 2

let off = self.seq.len_ghost() - 1int;

self.seq.get_mut_ghost(off).unwrap()

},

)

};

link_last.next = link_ptr;

self.last = link_ptr;

}

ghost! { self.seq.push_back_ghost(link_own.into_inner()) }; // 3

}Step 6: pop_front

Specify pop_front

Write the contract of pop_front.

Tip

- Use

Seq::pop_front.- We can use

matchin Pearlite.

Solution

#[ensures(match result {

None => (*self)@ == Seq::empty() && (^self)@ == Seq::empty(),

Some(x) => (*self)@.len() > 0 && x == (*self)@[0] && (^self)@ == (*self)@.pop_front()

})]Verify pop_front.

As before, we must modify the function to manipulate pointer permissions.

- Pop the first permission from

self.seq. (Hint: useSeq::pop_front_ghost.) - Replace

Box::from_raw, which casts a pointer to aBox, withPerm::to_box, which also requires the permission protecting the pointer.

Solution

pub fn pop_front(&mut self) -> Option<T> {

if self.first.is_null() {

return None;

}

let own = ghost! { self.seq.pop_front_ghost().unwrap() }; // 1

let link = unsafe { *Perm::to_box(self.first as *mut Link<T>, own) }; // 2

self.first = link.next;

if self.first.is_null() {

self.last = std::ptr::null_mut();

}

Some(link.value)

}Step 7: push_front

Follow the same recipe as push_back and pop_front.

Conclusion

We now have a verified implementation of linked lists. This data structure makes use of unsafe primitives, and Creusot formally verifies that their safety conditions are satisfied.

Basic concepts

Every Creusot macro will erase themselves when compiled normally: they only exist when using cargo creusot.

If you need to have Creusot-only code, you can use the #[cfg(creusot)] attribute.

Note that you must explicitly use the creusot_std crate in your code (which should be the case once you actually prove things, but not necessarily when you initially set up a project), such as with the line:

use creusot_std::prelude::*;or you will get a compilation error complaining that the creusot_std crate is not loaded.

requires and ensure

Most of what you will be writing with creusot will be requires and ensures clauses. That is: preconditions and postconditions.

Together, those form the contract of a function. This is in essence the “logical signature” of your function: when analyzing a function, only the contract of other functions is visible.

Preconditions with requires

A precondition is an assertion that must hold when entering the function. For example, the following function accesses a slice at index 0:

fn head(v: &[i32]) -> i32 {

v[0]

}So we must require that the slice has at least one element:

#[requires(v@.len() >= 1)]

fn head(v: &[i32]) -> i32 {

v[0]

}Note the view (@) operator: it is needed to convert the Rust type &[i32] to a logical type Seq<i32>. Else, we could not call [T]::len, which is a program function (and not a logical one).

To learn more, see the chapter on Pearlite and Views.

Postconditions with ensures

A postcondition is an assertions that is proven true at the end of the function. The return value of the function can be accessed via the result keyword.

In the case of the example above, we want to assert that the returned integer is the first of the slice:

#[requires(v@.len() >= 1)]

#[ensures(v@[0] == result)]

fn head(v: &[i32]) -> i32 {

v[0]

}Note that we:

- use the

@operator on the slice to get aSeq<i32> - we can then index this

Seq<i32>to get ai32.

Loop invariants

Note

The word “invariant” has a lot of different meanings in program verification. Even within Creusot, there are at least three unrelated meanings, and we avoid ambiguity by always qualifying the noun “invariant” accordingly:

- Loop invariants, discussed in this chapter.

- Type invariants.

- Resource invariants, for separation logic reasoning about shared resources. In Creusot, we further distinguish “atomic invariants” and “non-atomic invariants”; see the module

creusot_std::ghost::invariant.

When writing a loop (be it for, while or loop), you will generally need to specify a loop invariant,

that is an assertion that stays true for the duration of the loop.

For example, consider the following program:

#[ensures(result == n)]

fn loop_add(n: u64) -> u64 {

let mut total = 0;

while total < n {

total += 1;

}

total

}This program needs a loop invariant: even though its proof seems obvious to us, it is not for Creusot. What Creusot knows is:

- Any variable not referenced in the loop is unchanged at the end (here this is obvious because

nis immutable, but it might be relevant in a more complicated program). - At the end of the loop, the loop condition is false: here

total >= n.

We still need to know that total <= n to get result == n.

Use the #[invariant]

attribute to write loop invariants:

#[ensures(result == n)]

fn loop_add(n: u64) -> u64 {

let mut total = 0;

#[invariant(total <= n)]

while total < n {

total += 1;

}

total

}This is now provable !

Like

requiresandensures,invariantmust contain a pearlite expression returning a boolean.

Verification conditions

The reason why loop invariants are useful is that they enable reducing the verification problem to verifying loop-free fragments of code.

For example, consider a function with one while loop:

#[requires(PRE)]

#[ensures(POST(result))]

fn f(x: A) -> B {

CODE_BEFORE_LOOP;

#[invariant(INVARIANT)]

while CONDITION {

LOOP_BODY;

}

CODE_AFTER_LOOP

}To prove that this function satisfies its contract, we only have to verify three simpler subprograms (here in pseudo-code).

-

The code before the loop must establish the invariant, assuming the precondition.

assume! { PRE } CODE_BEFORE_LOOP; assert! { INVARIANT } -

The loop body must preserve the invariant, assuming that the loop condition is

true.assume! { INVARIANT && CONDITION } LOOP_BODY assert! { INVARIANT } -

The code after the loop must establish the postcondition, assuming that the invariant holds and the loop condition is

false.assume! { INVARIANT && !CONDITION } let result = { CODE_AFTER_LOOP }; assert! { POST(result) }

If you don’t provide a loop invariant, it defaults to true, and you are left with very

little information to reason about the loop body and the code after the loop.

Note that this is an oversimplified example. As mentioned in the previous section, facts about variables that are not referenced by the loop body are automatically preserved and don’t need to be mentioned explicitly in the invariant.

for loop invariants: produced

Invariants of for loops have access to a special produced variable which

contains the sequence of elements produced by the iterator, in a snapshot.

#[invariant(I)]

for PAT in ITER {

BODY

}The above desugars to the following, where produced is explicitly defined and in scope in I:

let mut it = ::std::iter::IntoIterator::into_iter(ITER);

let iter_old = snapshot! { it };

let mut produced = snapshot! { ::creusot_std::logic::Seq::empty() };

#[invariant(I)]

loop {

match ::std::iter::Iterator::next(&mut it) {

Some(elem) => {

produced = snapshot! { produced.inner().concat(::creusot_std::logic::Seq::singleton(elem)) };

let PAT = elem;

BODY

},

None => break,

}

}Compiling with rustc

Make sure that functions that contain #[invariant(...)] attributes also have

an #[ensures(...)] or #[requires(...)] attribute.

You can always add #[ensures(true)] as a trivial contract.

That enables compilation (cargo build) with a stable Rust compiler,

preventing the following error:

error[E0658]: attributes on expressions are experimental

Indeed, the #[invariant(...)] attribute on loops is only allowed by unstable features

(stmt_expr_attributes, proc_macro_hygiene). For compatibility with stable Rust,

the requires and ensures macros remove #[invariant(...)]

attributes during normal compilation.

Variants

A variant clause can be attached either to a function like ensures, or requires or to a loop like invariant, it should contain a strictly decreasing expression which can prove the termination of the item it is attached to.

proof_assert!

At any point in the code, you may want to insert an arbitrary verification condition. This can be useful:

- For debugging, to ensure that a property indeed holds at a certain point of the program.

- To help the provers in specific cases.

To do this, Creusot gives you the proof_assert! macro:

fn f() {

// ...

let x = 1;

let y = 2;

proof_assert!(x@ + y@ == 3);

// ...

}

proof_assertmust contain a pearlite expression returning a boolean.

Trusted

The trusted marker lets Creusot trust the implementation and specs.

More specifically, you can put #[trusted] on a function like the following:

#[trusted]

#[ensures(result == 42u32)]

fn the_answer() -> u32 {

trusted_super_oracle("the answer to life, the universe and everything")

}TODO: trusted traits

Representation of types

Creusot translates Rust code to Why3. But Rust types don’t always exist in Why3, and would not have the same semantics: thus we need to map each Rust type to a Why3 type.

Base types

Most type have a very simple interpretation in Why3:

-

The interpretation for a scalar type (

i32,bool,f64, …) is itself. -

The interpretation of

[T]isSeq<T>, the type of sequences. -

The interpretation of

&Tis the interpretation ofT.Creusot is able to assume that

Tand&Tbehave the same, because of the “shared xor mutable” rule of Rust: we won’t be able to change the value (interior mutability is handled by defining a special model for e.g.Cell<T>), so we may as well be manipulating an exact copy of the value. -

The interpretation of

Box<T>is the interpretation ofT.This is because a

Boxuniquely own its content: it really acts exactly the same asT. -

Structures and enums are interpreted by products and sum types.

-

The interpretation of

&mut Tis a bit more complicated: see the next section.

Mutable borrows

In Creusot, mutable borrows are handled via prophecies. A mutable borrow &mut T contains:

- The current value (of type

T) written in the borrow. - The last value written in the borrow, called the prophecy.

This works in the underlying logic by performing two key steps:

- When the borrow is created, the prophecy is given a special

anyvalue. We don’t know it yet, we will trust the logic solvers to find its actual value based on later operations. - When dropping the borrow, Creusot adds the assumption

current == prophecy. We call that resolving the prophecy.

Final reborrows

The above model is incomplete: in order to preserve soundness (see the Why is this needed ? section), we need to add a third field to the model of mutable borrows, which we call the id.

Each new mutable borrow gets a unique id, including reborrows. However, this is too restrictive: with this, the identity function cannot have its obvious spec (#[ensures(result == input)]), because a reborrow happens right before returning.

To fix this, we introduce final reborrows:

A reborrow is considered final if the prophecy of the original borrow depends only on the reborrow. In that case, the reborrow id can be inherited:

- If this is a reborrow of the same place (e.g.

let y = &mut *x), the new id is the same. - Else (e.g.

let y = &mut x.field), the new id is deterministically derived from the old.

Examples

In most simple cases, the reborrow is final:

let mut i = 0;

let borrow = &mut i;

let reborrow = &mut *borrow;

// Don't use `borrow` afterward

proof_assert!(reborrow == borrow);

#[ensures(result == x)]

fn identity<T>(x: &mut T) -> &mut T {

x

}It even handles reborrowing of fields:

let mut pair = (1, 2);

let mut borrow = &mut pair;

let borrow_0 = &mut borrow.0;

proof_assert!(borrow_0 == &mut borrow.0);However, this is not the case if the original borrow is used after the reborrow:

let mut i = 0;

let borrow = &mut i;

let reborrow = &mut *borrow;

*borrow = 1;

proof_assert!(borrow == reborrow); // unprovable

// Here the prophecy of `borrow` is `1`,

// which is a value completely unrelated to the reborrow.Or if there is an indirection based on a runtime value:

let mut list = creusot_std::vec![1, 2];

let borrow: &mut [i32] = &mut list;

let borrow_0 = &mut borrow[0];

proof_assert!(borrow_0 == &mut borrow[0]); // unprovableWhy is this needed ?

In essence, to prevent the following unsound code:

pub fn unsound() {

let mut x: Snapshot<bool> = snapshot! { true };

let xm: &mut Snapshot<bool> = &mut x;

let b: &mut Snapshot<bool> = &mut *xm;

let bg: Snapshot<&mut Snapshot<bool>> = snapshot! { b };

proof_assert! { ***bg == true && *^*bg == true };

let evil: &mut Snapshot<bool> = &mut *xm;

proof_assert! { (evil == *bg) == (*^evil == true) };

*evil = snapshot! { if evil == *bg { false } else { true } };

proof_assert! { **evil == !*^evil };

proof_assert! { **evil == !**evil };

}If borrows are only a pair of current value/prophecy, the above code can be proven, and in particular it proves **evil == !**evil, a false assertion.

Pearlite

Pearlite is the language used in:

- contracts (

ensures,requires,invariant,variant) proof_assert!- the

pearlite!macro

It can be seen as a pure, immutable fragment of Rust which has access to a few additional logical operations and connectives. In practice you have:

- Base Rust expressions: matching, function calls, let bindings, binary and unary operators, tuples, structs and enums, projections, primitive casts, and dereferencing

- Logical Expressions: quantifiers (

forallandexists), logical implication==>, logical equalitya == b, labels - Rust specific logical expressions: access to the final value of a mutable reference

^, access to the view of an object@

Logical implication

Since => is already a used token in Rust, we use ==> to mean implication:

proof_assert!(true ==> true);

proof_assert!(false ==> true);

proof_assert!(false ==> false);

// proof_assert!(true ==> false); // incorrectQuantifiers

The logical quantifiers ∀ and ∃ are written forall and exists in Pearlite:

#[requires(forall<i: Int> i >= 0 && i < list@.len() ==> list@[i] == 0)]

fn requires_all_zeros(list: &[i32]) {

// ...

}Logic functions

Functions marked with #[logic] can be used in specifications (requires/ensures and invariant) and in snapshot!, but cannot be called from normal Rust code.

Typically, logic functions manipulate variables of logical model types such as Int and Seq<Int> rather than normal Rust types such as i32 and &[i32].

Logical function use normal Rust syntax, but the operators are the logical ones: == in a #[logic] function does not mean PartialEq::eq, but is rather logical equality.

The full pearlite syntax can be used by opening a pearlite! { ... } block.

Logical functions can only call other logical functions, not program functions (and vice-versa).

The #[logic] attribute may take additional modifiers in parentheses, like #[logic(open, prophetic)].

Those attributes are described in the following subsections.

Recursion

When you write recursive logical functions, you have to show that the function terminates.

There are two ways to do so:

-

If the recursion has a structural variant, you have nothing to do. A structural variant is when you

matchon a value, and only use sub-parts of the match in the recursive call:enum List { Nil, Cons(Box<Self>) } #[logic] fn length(l: List) -> Int { match l { List::Nil => 0, List::Cons(tail) => 1 + length(*tail), } }In this case, the recursion is accepted by Why3 automatically.

-

Else, you need to add a

#[variant(EXPR)]attribute to the function. Creusot will then check that the expressionEXPRstrictly decreases (in a known well-founded order) at each recursive call.The type of

EXPRshould implement theWellFoundedtrait.

Examples

Basic example:

#[logic]

fn logic_add(x: Int, y: Int) -> Int {

x + y

}

#[requires(x < i32::MAX)]

#[ensures(result@ == logic_add(x@, 1))]

pub fn add_one(x: i32) -> i32 {

x + 1

}Pearlite block:

#[logic]

fn all_ones(s: Seq<i32>) -> bool {

pearlite! {

forall<i: Int> i >= 0 && i < s.len() ==> s[i]@ == 1

}

}

#[ensures(all_ones(result@))]

#[ensures(result@.len() == n@)]

pub fn make_ones(n: usize) -> Vec<i32> {

creusot_std::vec![1; n]

}Recursion:

TODOProphetic:

TODOVisibility of logical functions

By default, logic functions are opaque outside the module they are defined in (in other words, they are only open at the module level).

When a function is opaque, only its pre- and postconditions are visible.

This is useful if the function is only used to express (and prove) that the preconditions imply the postconditions, and we do not care about the result (a lemma 1).

However, if you do want to use the result in a specification outside the module (e.g. if you are using it as a predicate in one or more contracts), you use the open modifier.

It takes an optional argument, similar to pub, e.g. you could specify that a function is to be #[logic(open(super))] or #[logic(open(crate))].

mod inner {

// ensures in needed here, as code outside the module will not see the body

// of this function

#[ensures(result == x + 1)]

#[logic]

pub fn adds_one_closed(x: Int) -> Int { x + 1 }

// no need for `ensures` here!

#[logic(open)]

pub fn adds_one_open(x: Int) -> Int { x + 1 }

}Additionally, you can use the opaque modifier to make the logical function fully opaque, even to other functions in the module.

In this case, you cannot attach a specification to the function: you only know that it returns some value (note that this is sound, as all types are inhabited in the logic).

This is one of the only places where you can use the dead special keyword, which does nothing but indicate that the function has no implementation.

#[logic(opaque)]

fn generate_int() -> Int {

dead

}-

The Dafny tutorial is a pretty good resource on how to use lemmas. ↩

Prophetic functions

As seen in the chapter on mutable borrow, a mutable borrow contains a prophetic value, whose value depends on future execution. In order to preserve the soundness of the logic, #[logic] functions are not allowed to observe that value: that is, they cannot call the prophetic ^ operator.

If you really need a logic function to use that operator, you need to mark it with #[logic(prophetic)] instead. In exchange, this function cannot be called from snapshot!.

A normal #[logic] function cannot call a #[logic(prophetic)] function.

Lemmas and laws

Lemmas

A lemma is a logical function that is useful because of its pre and postconditions, rather than the value it returns.

For example, suppose that as part of a proof, we want to prove that x + y > 0 ==> x > 0 || y > 0.

We can define it as a logical function:

#[logic]

#[requires(x + y > 0)]

#[ensures(x > 0 || y > 0)]

fn add_gt_zero(x: Int, y: Int) {}This lemma is easily proved by SMT solvers, so we don’t need to give it a body. Sometimes though, it may be useful to define a body to guide the proof: in this toy example, we could do

#[logic]

#[requires(x + y > 0)]

#[ensures(x > 0 || y > 0)]

fn add_gt_zero(x: Int, y: Int) {

if x > 0 {} else {

proof_assert!(y >= x + y);

}

}If x > 0, the proof is over; else, we know by arithmetic that y >= x + y, so by transitivity of the order it must be > 0.

Lemmas as trait properties

A lot of traits impose greater constraint on their operation than can be seen in the type system.

In this case, additional constraint may be defined as lemmas. For example, we may want to define a trait for commutative operations:

trait Commutative: Sized {

#[logic]

fn op(self, other: Self) -> Self;

#[logic]

#[ensures(self.op(other) == other.op(self))]

fn commutative(self, other: Self);

}To ensure commutativity in a way that makes it easy on implementors, we define it as an additional lemma commutative.

Implementors of this trait must then prove that commutativity holds for any self and other.

Laws

The above example has a potential issue: when using op, we don’t automatically know that it is commutative: we have to use the lemma first, to import it into the proof context:

#[logic]

fn foo<T: Commutative>(x: T, y: T) {

let z = x.op(y);

// let _ = x.commutative(y);

proof_assert!(z == y.op(x)); // does not work without uncommenting the above line

}To make this easier, we can define commutativity as a law: a logical function that will get imported into the context whenever a function in the same trait is used.

trait Commutative: Sized {

#[logic]

fn op(self, other: Self) -> Self;

#[logic(law)]

#[ensures(self.op(other) == other.op(self))]

fn commutative(self, other: Self);

}

#[logic]

fn foo<T: Commutative>(x: T, y: T) {

let z = x.op(y);

proof_assert!(z == y.op(x)); // Works!

}Views as models of types

It is generally convenient to map a Rust type to its logical model. This logical model is the type that specifications and clients then use to describe values of this type in the logic.

In Creusot, this is provide using the creusot_std::View trait, providing a view method mapping the type to a ViewTy associated type for the model.

Specifications can then use the @ operator as a syntactic sugar for .view() on a type that implements View.

For example, the following gives a spooky data type MyPair<T, U> a nice pair model.

struct MyPair<T, U> {

fst: T,

snd: U,

}

impl<T, U> View for MyPair<T, U> {

type ViewTy = (T, U);

#[logic(open)]

fn view(self) -> Self::ViewTy {

(self.fst, self.snd)

}

}

#[ensures(result@ == (a, b))]

fn my_pair<T, U>(a: T, b: U) -> MyPair<T, U> {

MyPair(a, b)

}Termination

By default, Creusot does not require that program functions terminate, which may lead to surprising situations:

#[ensures(result@ == 42)]

fn nonsense() -> u64 {

while true {}

1

}This can be avoided at the cost of more complicated verification, by adding the check(terminates) attribute to a function:

#[check(terminates)]

#[ensures(result@ == 42)]

fn nonsense() -> u64 { // Fails to compile now !

while true {}

1

}A function with the check(terminates) attribute cannot:

-

Call a non-

terminatesfunction. -

Use a loop construct (

for,while,loop). This restriction may be lifted in the future. -

Use simple recursion without the

variantattribute.This means that this function will not be accepted:

#[check(terminates)] fn f(x: u32) -> bool { if x == 0 { false } else { f(x - 1) } }But this one will (the variant will be checked by why3):

#[check(terminates)] #[variant(x)] fn f(x: u32) -> bool { if x == 0 { false } else { f(x - 1) } } -

Use mutual recursion, like in the following example:

#[check(terminates)] fn f() { g() } // Error: mutually recursive functions #[check(terminates)] fn g() { f() }

Mutual recursion through traits

Traits complicate the recursion analysis. Indeed, if we have a function like

trait Tr {

fn f();

}

fn g<T: Tr>() {

<T as Tr>::f();

}It isn’t possible to know ahead of time which instance of f will be called.

Thus, Creusot makes the decision to check recursion at instantiation time: the above example compiles, but

trait Tr {

fn f();

}

fn g<T: Tr>() {

<T as Tr>::f();

}

impl Tr for i32 {

fn f() {

g::<i32>();

}

}does not, because we know that g::<i32> calls <i32 as Tr>::f(), causing a cycle.

Dependencies

The recursion check explores the body of the functions in the current crate, but it cannot do so with the dependencies, whose function bodies are not visible.

Thus, it assumes two things:

- The recursion check passed on the dependencies of the current crate.

- If a function in a dependency has a trait bound, the recursion check pessimistically assumes that all the functions of the trait are called.

Example:

// dependency/src/lib.rs

trait Tr {

fn f();

}

fn g<T: Tr>() {

// It does not matter if `<T as Tr>::f` is called or not, since we cannot see it

}

// lib.rs

impl Tr for i32 {

fn f() {

g::<i32>(); // Error !

}

}Snapshots

A useful tool to have in proofs is the Snapshot<T> type (creusot_std::Snapshot). Snapshot<T> is:

- a zero-sized-type

- created with the

snapshot!macro - whose model is the model of

T - that can be dereferenced in a logic context.

Example

They can be useful if you need a way to remember a previous value, but only for the proof:

#[ensures(array@.permutation_of((^array)@))]

#[ensures(sorted((^array)@))]

pub fn insertion_sort(array: &mut [i32]) {

let original = snapshot!(*array); // remember the original value

let n = array.len();

#[invariant(original@.permutation_of(array@))]

#[invariant(...)]

for i in 1..n {

let mut j = i;

#[invariant(original@.permutation_of(array@))]

#[invariant(...)]

while j > 0 {

if array[j - 1] > array[j] {

array.swap(j - 1, j);

} else {

break;

}

j -= 1;

}

}

proof_assert!(sorted_range(array@, 0, array@.len()));

}

#[logic]

fn permutation_of(s1: Seq<i32>, s2: Seq<i32>) -> bool {

// ...

}

#[logic]

fn is_sorted(s: Seq<i32>) -> bool {

// ...

}Ghost code

Sometimes, you may need code that will be used only in the proofs/specification, that yet still obeys the typing rules of Rust. In this case, snapshots are not enough, since they don’t have lifetimes or ownership.

This is why there exists a separate mechanism: ghost code.

ghost! and Ghost<T> are the counterparts of snapshot! and Snapshot<T>.

ghost! blocks

At any point in the code, you may open a ghost! block:

ghost! {

// code here

}In ghost! block, you may write any kind of Rust code, with the following restrictions :

- ghost code must terminate (see termination for details)

- all functions called must have the

#[check(ghost)]attribute - When reading an outer variable, the variable must be of type

Ghost<T>, or implementCopy - When writing an outer variable, the variable must be of type

Ghost<T>orSnapshot<T> - The output of the

ghost!block will automatically be wrapped inGhost::new

Those restriction exists to ensure that ghost code is erasable: its presence or absence does not affect the semantics of the actual running program, only the proofs.

Ghost<T>

The Ghost<T> type is the type of “ghost data”. In Creusot, it acts like a Box<T>, while in normal running code, it is an empty type. It has the same View as the underlying type, meaning you can use the @ operator directly.

The only restriction of Ghost<T> is that it may not be dereferenced nor created in non-ghost code.

Examples

- Creating and modifying a ghost variable:

let mut g = ghost!(50);

ghost! {

*g *= 2;

};

proof_assert!(g@ == 100);- Calling a function in ghost code:

#[check(ghost)]

#[requires(*g < i32::MAX)]

#[ensures((^g)@ == (*g)@ + 1)]

fn add_one(g: &mut i32) {

*g += 1;

}

let mut g = ghost!(41);

ghost! {

add_one(&mut *g);

};

proof_assert!(g@ == 42);- Using a ghost access token:

struct Token;

struct Data {

// ...

}

impl Data {

fn new() -> (Data, Ghost<Token>) { /* */ }

fn read(&self, token: &Ghost<Token>) -> T { /* */ }

fn write(&self, t: T, token: &mut Ghost<Token>) { /* */ }

}Ghost structures

Using imperative data structures in ghost code

Usual imperative structures like Vec, HashMap or HashSet cannot be used in ghost code. To be precise, you may notice that functions like Vec::push are not marked with the #[check(ghost)] attribute, and so they cannot be called in ghost code.

This is because this function (and other like it) allocate memory, which on the actual machine, is finite. This currently translates to a possible inconsistency when using Vec in ghost code:

use creusot_std::{proof_assert, ghost};

ghost! {

let mut v = Vec::new();

for _ in 0..=usize::MAX as u128 + 1 {

v.push(0);

}

proof_assert!(v@.len() <= usize::MAX@); // by definition

proof_assert!(v@.len() > usize::MAX@); // uh-oh

}This case might be forbidden in the future by adding a stronger precondition to Vec::push, but the point still stands: the capacity of a ghost vector should be infinite.

Ghost structures

As such, ghost code uses the mathematical structures Seq, FMap and FSet, and adds program functions onto them.

The above snippet becomes:

use creusot_std::{proof_assert, ghost, Int, logic::Seq};

ghost! {

let mut s: Seq<Int> = Seq::new();

for _ in 0..=usize::MAX as u128 + 1 {

s.push_ghost(0);

}

// proof_assert!(s.len() <= usize::MAX@); // fails

proof_assert!(s.len() > usize::MAX@);

}A few things to note:

Seq,FMapandFSetare the counterparts forVec,HashMapandHashSetrespectively. They all live in thelogicmodule.- Since

sin directly the logical typeSeq, we don’t need the view operator@. - To avoid name clashes, these additional “ghost” functions are almost all suffixed with

_ghost. See the documentation for each type to know the available methods, ghost and logical.

Int in ghost

You can manipulate values of type Int in ghost code, by using the int suffix on integer literals:

ghost! {

let x = 42int;

let y = 58int;

assert!(x + y == 100int);

};Ghost containers return their length as an Int, and Seq is indexed by Int as well:

ghost! {

let s: Seq<_> = ...;

let m: FMap<_, _> = ...;

let len: Int = m.len_ghost();

let x = s[len + 3int];

};Type Invariants

Overview

Defining a type invariant allows you to constrain a data type’s set of valid values with a logical predicate that all values must satisfy. During verification, Creusot enforces that all type invariants are preserved across functions. Inside a function, values subject to type invariants may temporarily break their invariants as long as each value’s invariant is restored before the value can be observed by another function.

Type invariants were added to Creusot as part of a Master’s thesis available here.

Defining Type Invariants

To attach an invariant to a type, you implement the Invariant trait provided by Creusot.

Here is an example:

struct SumTo10 {

a: i32,

b: i32,

}

// The type invariant constrains the set of valid `SumTo10`s to

// only allow values where the sum of both fields is equal to 10.

impl Invariant for SumTo10 {

#[logic]

fn invariant(self) -> bool {

pearlite! {

self.a@ + self.b@ == 10

}

}

}Enforcement of Type Invariants

Creusot enforces type invariants on function boundaries by generating additional pre- and postconditions based on the types of a function’s arguments and return value. The type invariants of a function’s arguments are treated as additional preconditions and a type invariant of the return value corresponds to an extra postcondition. Here is an example:

// `inv` generically refers to the invariant of some value

#[requires(inv(x))] // generated by Creusot

#[ensures(inv(result))] // generated by Creusot

fn foo(x: SumTo10) -> SumTo10 {

x

}These generated pre- and postconditions require you to prove the invariants of any values used as arguments in function calls or returned values.

Besides the proof obligations at function boundaries, you must also prove the type invariants of mutably borrowed values when the lifetimes of the created references end.

When creating a mutable reference r, Creusot requires you to prove the type invariant of its current value at the end of r’s lifetime, since r might have been used to break the invariant of the borrowed value.

This lets Creusot assume the invariant of the final value ^r holds, simplifying the reasoning about mutable references.

Here is an example:

fn swap() {

let mut s = SumTo10 { a: 3, b: 7 }

let r = &mut s;

// Creusot can prophetically assume inv(^r) holds:

proof_assert! { inv(^r) };

let tmp = r.a;

*r.a = r.b;

*r.b = tmp;

// The lifetime of r ends: We must prove inv(*r)

proof_assert! { inv(v) }; // provable since v = ^r = *r

}Structural Invariants

To determine the invariant of a particular type, Creusot considers:

- User-provided definitions, defined with the

Invarianttrait. - Invariants that can be derived automatically based on the type’s definition.

The second category is called structural invariants. When neither an explicit definition exists, nor a structural invariant, the type has the trivial invariant, which does not impose any constraints on the set of valid values.

Here are some examples demonstrating structural invariants of various types:

Type of x | Invariant inv(x) |

|---|---|

bool, u8, i32, ... | true |

&mut Foo | inv(*x) && inv(^x) |

&Foo | inv(*x) |

Box<Foo> | inv(*x) |

*const Foo, *mut Foo | true |

(Foo, Bar) | inv(x.0) && inv(x.1) |

struct Foo { f: Bar } | inv(x.f) |

enum Foo { A(Bar), B(Baz) } | match x { A(y) => inv(y), B(z) => inv(z) } |

Vec<Foo> | inv(x[0]) && ... && inv(x[x.len()-1]) |

Logical functions

Creusot decides not to add type invariants to the pre- and postconditions of logical functions. This means that the following is not provable:

#[logic]

#[ensures(x.a@ + x.b@ == 10)]

fn no_inv_in_logic(x: SumTo10) {}Even though the same function in program is provable:

#[ensures(x.a@ + x.b@ == 10)]

fn inv_in_program(x: SumTo10) {}Erasure check

Verifying functions with Creusot requires modifying their code to add attributes, assertions, ghost code, etc.. This creates a gap between the function that is verified and the function that is compiled and run. The disconnect is two-fold:

- The verified function is different from the original function. One may still want to keep using the original function for various reasons, including avoiding a dependency on Creusot.

- Even if you compile the verified function, that relies on erasing Creusot annotations, which may affect trait resolution and result in compiling a different function than the one that was verified by Creusot.

To bridge that gap, the #[erasure(...)] attribute maintains a tight connection

between the verified function and the original function.

Overview

The attribute #[erasure(f)] is put on a function definition.

It asserts that the annotated function f2 (to be verified by Creusot) and the target f

(to be compiled) have the same runtime behavior.

This is a syntactic check that tries to simply match the bodies of f and f2 with each other

modulo small code transformations to ignore purely logical constructs.

#[erasure(f)]

fn f2(x: A) {

/* ... */

}The #[erasure] check performs the following operations.

- Erase

GhostandSnapshotvariables,ghost!,snapshot!, andproof_assert!blocks,#[ensures],#[requires],#[invariant]attributes. - Replace called functions with their own

#[erasure]. - Equate up to A-normal form.

#[trusted] functions skip the #[erasure] check.

Additional rules for pointers:

Perm::as_ref(ptr)erases to&*ptr(pointer-to-reference coercion).Perm::as_mut(ptr)erases to&mut *ptr(pointer-to-reference coercion).Perm::from_ref(r)erases tor as *const T(reference-to-pointer coercion).Perm::from_mut(r)erases tor as *mut T(reference-to-pointer coercion).

Example

Consider the following generic example of “unverified code”.

The function h calls two functions f and g:

fn h(x: A) {

g(f(x))

}

fn f(x: A) -> B { /* ... */ }

fn g(y: B) { /* ... */ }“Verifying” these functions with Creusot may involve introducing ghost arguments, ghost blocks, assertions, etc., resulting in code that looks as follows.

#[erasure(h)]

#[requires(...)]

#[ensures(...)]

fn h2(x: A) {

let (y, i) = f2(x);

ghost!(...);

g2(y, i)

}

#[erasure(f)]

fn f2(x: A) -> (B, Ghost<I>) { /* ... */ }

#[erasure(g)]

fn g2(y: B, i: Ghost<I>) { /* ... */ }The attribute #[erasure(h)] checks that h2 behaves the same as the previous h if we ignore ghost code.

In order to do this check, Creusot performs a couple of transformations to the body of h.

First, erase ghost blocks, ghost variables, and assertions:

fn h2(x: A) {

let (y, _) = f2(x);

g2(y, _)

}Replace f2 with its erasure f, g2 with its erasure g (as indicated by their own #[erasure] attributes).

The erasure of f2 also replaces its result tuple with its only non-ghost component.

fn h2(x: A) {

let y = f(x);

g(y)

}Before comparing h2 and h, we put them both in A-normal form. Here, h2 is simple and already in A-normal form.

The body f(g(x)) of the function h gets rewritten as follows.

fn h(x: A) {

let y = f(x);

g(y)

}Now h2 and h are identical, so the #[erasure(h)] check succeeds.

Usage

Intra-crate checks

When #[erasure(f)] mentions a function f defined in the same crate

as the annotated function, the erasure check works simply as you would expect.

Cross-crate checks

When #[erasure(f)] mentions a function f from another crate,

#[erasure] check failures are reported as warnings by default

because they require some setup to work.

The #[erasure] check requires compiling your whole project twice: the first time to know what definitions

need to be checked, and the second time to get dependencies to export those definitions. The reason is that

#[erasure] compares THIR ASTs, which exist only during the compilation of the crate containing those definitions.

The required definitions are stored as binary blobs in the folder _creusot_erasure so that they persist

when removing target/creusot to force a rebuild.

cargo creusot

rm -r target/creusot # Force rebuilding from scratch

cargo creusot --erasure-check

To keep the metadata for #[erasure] checks up to date, you must recompile twice whenever you add new

#[erasure] annotations or you update a dependency.

Due to this, #[erasure] checks give different errors depending on whether you have rebuilt your

project from scratch at least once (“missing bodies” vs. “the actual check failed”).

For that reason, these failures are reported as warnings by default.

Use the option --erasure-check to report them as errors instead.

The variants of this option are:

--erasure-check=no: disable#[erasure]checks;--erasure-check=warn(default): report#[erasure]check failures as warnings;--erasure-check(or--erasure-check=error): report#[erasure]check failures as errors.

Using core and std

When #[erasure(f)] mentions a function f from core or std, you must use

-Zbuild-std to get access to their THIR. Also make sure to have rust-src in your toolchain.

rustup component add rust-src --toolchain $MY_TOOLCHAIN

Private functions

It is also possible to name a private function using the private keyword

followed by the full path to the private function:

#[erasure(private crate_name::path::to::f)]Nested functions

#[erasure] automatically takes nested functions into account.

fn f() {

fn inside_f() {}

inside_f()

}

#[erasure(f)]

fn g() {

fn inside_f() {}

inside_f()

}The inner function of g does not need an #[erasure] attribute,

but it must have the same name as its counterpart in f.

Ghost functions

Ghost functions are those that may appear outside of ghost blocks

but are completely eraseable. The main examples are Ghost::split

and Ghost::borrow. They are identified by the attribute #[erasure(_)].

#[trusted]

#[erasure(_)]

fn split<T, U>(g: Ghost<(T, U)>) -> (Ghost<T>, Ghost<U>) { /* ... */ }Known limitations

Formal verification provides strong guarantees about your code. Nevertheless, it is important to be aware of the limits of what one has specified. Creusot users should take note of the following limitations.

Some panics are allowed

The Vec methods that increase capacity (push, insert, extend, etc.)

panic if the capacity overflows. The current contracts in creusot-std

do not prevent this.

Because Vec is such a fundamental type, bounding

its length is quite cumbersome. Moreover, you will probably run out of memory

(another kind of failure that Creusot does not prevent) before the capacity overflows.

There remains one notable blind spot: a Vec of a zero-sized type enables